[Report adopted by the National Committee of the Socialist Workers Party, June 12, 1983. For more information see the booklet Croatian Nationalism & the Fight for Socialism.]

The general background to this report is the growing involvement of the party with a whole number of migrant communities. This involvement takes the form of general political relations — solidarity work, political discussions, etc. — and also of contact in the workplace, where comrades work alongside people from just about every migrant community.

A decisive task of Australian revolutionaries is to win the mass of migrant workers to the perspectives of socialism and to incorporate the most conscious elements in the revolutionary party. Unless and until this is done, it will not be possible to make a revolution in this country.

An important aspect of this work is familiarising ourselves with the main features of the recent history and politics of the country of origin of each migrant group. In the case of many migrant communities, or important sections of them, the situation in their homeland plays the predominant role in their thinking and outlook. We are bound to take this into account. This task is a very fruitful one for the party. It fits in with our internationalist outlook and forces us to make it more concrete and definite.

Our first contact with the Croatian Movement for Statehood, the HDP, and our growing collaboration with it, have forced the party to think more closely about our attitude to the Yugoslav workers state. What is the nature of the anti-bureaucratic revolution that is necessary there? What role will the struggle of the various nationalities play in that revolution? And in particular, what role will the Croatian struggle for freedom play in the Yugoslav political revolution?

The purpose of this report is to affirm the general line of the party’s work in relation to the HDP, to affirm and spell out in more detail our political position on Yugoslavia, the political revolution there, the role of the national question in that process, and especially the role of the Croatian struggle for freedom.

To understand the Croatian question today it is essential to have some idea of the historical background. In this report I want to outline the main trends of historical development and focus on certain key episodes that enable us to see more clearly the long historical tradition of Croatian nationalism and the nature of the present conflict between the Croatian nation and the Serbian-dominated Belgrade bureaucracy.

Origins of the Croat nation

The Croats and the Serbs first appear in the Balkans in the seventh century AD. The Byzantine emperor of the time invited these two Slav tribes to move into the area of the north-west Balkans to secure it against other migratory peoples threatening the empire based at Constantinople.

These tribes first took control of the Dalmatian coast and then settled in the territories that are, roughly, modern Croatia and Serbia.

After this settlement missionaries from the Western Catholic Church converted the Croats to Christianity and established the use of the Latin alphabet. This was really the beginning and a key element in the Western cultural and political orientation that distinguishes Croatia and Dalmatia from the Eastern-oriented bulk of the Balkan peninsula in the ensuing centuries.

The history of the Serbs has been very different from that of the Croats, mainly because they settled further to the east and the south. Serbia’s cultural and political orientation has been largely to the East.

This began in the ninth century, when the Eastern church began large-scale missionary work among the Serbs. Two famous Slav missionaries, Cyril and Methodius, helped convert the Serbs to Eastern Christianity. They also developed the Cyrillic alphabet, which has been used by the Serbs ever since.

In the early tenth century, the Croats established an independent kingdom, which lasted for almost two centuries. When the last native Croatian king, Zvonimir, died in 1089, Croatia established a union with Hungary, which essentially lasted for over 800 years.

The nature of this link varied over the years: Sometimes Croatia appears to be almost independent and at other times it appears to be completely subordinate, but it always retained a large amount of internal autonomy.

To the east, a strong Serbian state became consolidated toward the end of the 12th century. This state reached its greatest expansion and development under Stefan Dusan, who ruled from 1331 to 1355. Under his rule the Serbian empire grew to encompass what is now modern Serbia, Hercegovina, Montenegro, Albania, Macedonia, and northern Greece. At his death he described himself as “emperor of the Serbs and Greeks, Bulgars, and Albanians” and was preparing to take Constantinople, the last stronghold of the Byzantines. But the Serbian empire fell to pieces after his death.

Ottoman Empire

In the following era, south-eastern Europe was dominated by the empire of the Ottoman Turks.

The Ottomans originally came from a small emirate in what is now northern Turkey. In the first part of the 14th century, the Byzantine emperors used them as mercenaries in order to try to stem the Serbian advance. But in 1354 the Turks established themselves permanently on the European mainland on the Gallipoli peninsula. From there they spread out to conquer all the Balkans.

In 1389, the Turks won a decisive victory in their advance into the Balkans at the battle on the Field of Blackbirds at Kosovo in what is today an autonomous province in Serbia. The Christian army, led by the Serbs, was smashed and the Serbian leader, Lazar, was killed in the battle along with the flower of the Serb aristocracy.

By the end of the next century, almost all the Balkans were under Ottoman control. Montenegro — wild, desolate, and isolated — was the only part of the Balkans to escape Turkish domination from the 14th century on. While some Turkish forces penetrated there, they were never able to maintain themselves for long.

The Turkish advance continued after the subjugation of the Balkans. The Ottomans defeated a Hungarian army at Mohacs in 1526 and three years later besieged Vienna. Although unsuccessful, they maintained their empire in Europe against the Christian powers for the next 150 years. In addition to the Balkans, the Turks controlled most of Hungary and part of Croatia.

It’s worth noting several points about the nature of Turkish rule, which dominated the Balkans, in the main, for almost five centuries.

In the first period of Turkish rule, the conditions of the peasantry, the great mass of the Balkan people, were probably no worse, and possibly were even better, than in Western Europe. However, with the later decline of the Ottoman Empire, the oppression of the peasantry worsened sharply.

The other point to note is that the Turks exercised religious toleration. The Orthodox Christians were probably better treated by the Turks than they would have been by Catholic Christian rulers. Of course, the social position of Christians was inferior to that of Moslems, and to rise in the Turkish empire the Christian had to convert to Islam.

Most of the Balkan population retained their Catholic or Orthodox faith, but in Bosnia a significant number of the Slavs, mainly the feudal lords, converted to Islam. The mass of the peasantry remained Christian. Also, a majority of the Albanians (a non-Slav people who predate the arrival of the Slavs) converted to Islam.

The pattern of religious identification that exists today in Yugoslavia was, in its main lines, laid down in this period.

The decline of Turkish rule in Europe can be dated from 1683, when the Turks, for the second time, attempted to take Vienna. The siege was broken, and this marked the beginning of an Austrian resurgence.

In a series of campaigns over the next 50-odd years, the Austrian imperial armies won back control of Hungary, Croatia, and various other territories. The Treaty of Belgrade in 1739 established the Sava and Danube rivers as the border between Austria and Turkey. This lasted until 1878 (when Austria occupied Bosnia-Hercegovina).

From this point on, Croatia developed in the framework of the Austrian (later the Austro-Hungarian) Habsburg Empire, while Serbia developed in the framework of the Ottoman Empire and struggle against it.

This statement should be qualified by noting that during the wars between the Austrians and the Ottomans, significant numbers of Serbs had migrated northwards across the Danube and settled in southern Hungary, essentially in what is the Vojvodina autonomous region of modern Yugoslavia.

Early 19th century

In the early part of the 19th century, the Serbians rose up against the Ottomans. They were led by Kara George (“Black” George — so called because of his hair), a former peasant. This was the origin of the Karageorgevic dynasty, which ruled Yugoslavia in the 1920s and ’30s.

By 1806, after a succession of victories against the local and imperial armies, Serbia was liberated. But in 1812 the Turks made peace with the Russians and were able to send their forces back to crush Serbia. By the end of the next year, the revolt was over.

But a second revolt broke out in 1815, fueled by the Turkish repression. This was rapidly successful, and the Serbians were able to make a deal with the Turks and gain very wide autonomy. By the end of the 1820s, Serbia was effectively independent, with only a few Turkish garrisons remaining by treaty.

Another significant development took place in the early 19th century, this time on the western side of the Balkans. In 1809 Austria was forced to cede France a large strip of territory along the Adriatic — embracing Dalmatia, western Croatia, and some largely Slovene provinces above these.

Napoleon formed these into a unit called the Illyrian Provinces. Although French rule lasted only four years, the French Revolution made itself felt. The material condition of the area was much improved, and a significant impetus was given to the development of national feeling among the Croats and Slovenes. The Illyrian Provinces have been described as the first Yugoslav state since they contained within their borders Croats, Slovenes, and Serbs.

Revolutions of 1848-49

The next important development that we should consider in sketching the history of the Croats and Serbs was the great European revolutionary upsurge of 1848-49. This is especially important for us because it is tied up with the history of Marxism itself, in that Marx and Engels fought in this revolution and wrote extensively about it.

The 1830s and forties saw a growth of national consciousness and demand for democratic reform all across old-regime Europe. In Croatia in this period there were many manifestations of a growing national awareness. But this clashed with a similar process developing among the generally more economically and culturally advanced Hungarians or Magyars. What the Hungarians were demanding from Vienna, they were not prepared to concede to the Croats.

The name “Illyria” — taken to signify a union of Austrian South Slavs into their own state — was banned from being mentioned in public. In 1840 the Magyar national movement had succeeded in having Latin replaced by Magyar as the official language in Hungary. But in 1843-44, the Hungarian Diet decided that in Croatia also, Latin would be replaced by Magyar as the state language by the end of the decade.

A storm of protest from the Croats greeted this decision. Kossuth, the Hungarian leader, declared that he could not find Croatia on the map and said emphatically: “I know no Croatian nationality.”[1] Croat-Magyar relations rapidly deteriorated.

Then the revolution broke out. Following on news of the February 1848 uprising of the Paris masses against the monarchy, the people of Vienna rose up, demanding a liberalisation of the regime.

In Hungary the national movement flared up. The Hungarians demanded a representative government of their own. The Hungarian Diet moved to Budapest, the traditional capital of Hungary. Here it passed the so-called March laws, which aimed to curtail the extensive autonomy hitherto enjoyed by the Croats by incorporating Croatia into the Hungarian administrative system.

All these Hungarian moves went completely against the general national program of the Croats — that is, unification of all the Croat lands in the empire, autonomy in a federalised monarchy, and the use of their own language in public life.

Similar demands had been put forward, and rejected by the Hungarians, by the Serbs of southern Hungary.

In September of 1848, the emperor ordered Jelacic, the governor of Croatia, to restore order in Hungary. Jelacic crossed the Drava with an army of 40,000 Croats to pacify the rebellious Magyars. The Serbs of southern Hungary also armed themselves against the Magyars. These attempts were defeated by the Hungarians. (It should be noted that Serbia itself took no part in the events in the Habsburg Empire in this period.)

While the Austrian revolution, centred on German Vienna, was finally crushed in November of 1848, the situation in Hungary continued to radicalise. Early in 1849 the Hungarian Diet repudiated the Habsburgs, and Kossuth proclaimed a republic.

After a tremendous revolutionary struggle, during which they several times smashed the imperial armies and drove them out of Hungary, the Hungarians were finally defeated when tsarist Russia sent its troops into Hungary to help the emperor.

The counter-revolution dismembered Hungary. Croatia was put directly under the Austrian crown. The Serbs of southern Hungary were formed into an autonomous district. But the Croats and Serbs who had been loyal to the emperor did not get the liberty they wanted. The absolutist regime in Vienna ruled them just as harshly as it did the defeated Hungarians. A contemporary declared that the Hungarians “received as punishment what the other races received as reward”.

A liberal wit observed of the period of reaction that followed the defeat of the revolution that the Austrian regime rested on three armies: a standing army of soldiers, a kneeling army of worshippers, and a crawling army of informers.

The position taken by Marx and Engels in 1848-49 was based on the overriding necessity to drive forward the national-democratic revolutionary process on a European scale. The old feudal absolutist regimes, which were propping up obsolete economic, social, and political institutions, had to be smashed in the interests of historical progress. And behind the system of absolutist states stood the arch-reactionary power of tsarist Russia, the main enemy of progress in Europe throughout the 19th century.

Marx and Engels judged the various national movements in relation to which side they placed themselves on in this struggle.

In 1848-49, as Engels observed, “whereas the French, Germans, Italians, Poles and Magyars raised high the banner of the revolution, the Slavs one and all put themselves under the banner of the counter-revolution. In the forefront were the Southern Slavs … and behind them-the Russians …”[2]

Marx and Engels opposed the national movements of such Austrian South Slav peoples as the Croats and Serbs because, in the given instance, they acted as “Russian outposts” and fought for the counterrevolution. This stand of the South Slav national movements was definitely an error — it not only pitted them against the cause of historical progress, but in addition they received nothing from the imperial regime for which they fought.

But a large part of the responsibility for the reactionary stand taken by the Austrian South Slavs in 1848-49 must be taken by the Hungarian national movement with its national narrow-mindedness, chauvinism, and centralising tendencies.

|

| A legacy of history is the differing religious identifications in modern Yugoslavia. |

The ‘Eastern Question’

In 1867 the Habsburg regime was forced to reorganise the empire, and it concluded the so-called compromise with Hungary. Essentially this created two autonomous states, Austria and Hungary, linked by the one crown. The empire was now known as Austria-Hungary or the Dual Monarchy. One result of this restructuring was that Croatia was again affiliated to Hungary.

In the next year the compromise between Austria and Hungary was followed by an arrangement between Hungary and Croatia. This gave Croatia a limited autonomy under the Croatian parliament or Sabor at Zagreb. The mass of Croats strongly opposed this measure, feeling that it was far too limited. It gave Croatia only a small minority representation in the Hungarian parliament and no access to the central administration of the empire except through the Hungarian administration.

The history of the Balkans in the 19th century is concerned above all with the Eastern Question, that is, what system of states and alliances was to replace the decaying Turkish Empire in Europe. There were two aspects to this question: On the one hand there was the struggle of the oppressed Balkan peoples for freedom, and on the other there was the struggle of the European powers for hegemony in the region. The two main powers contending for domination in the region were Austria-Hungary and Russia.

The events of 1875-78 illustrate this very clearly. In 1875 the terribly oppressed Christian peasants of Bosnia rose up against the Turkish administration. Serbia and Montenegro declared war on the Turks, and the Bulgarians rose in revolt. The Serbians suffered defeat but in 1877 Russia, which always posed as the great protector of the Slav peoples, declared war on Turkey and was victorious by early the next year.

The war was ended formally by the Treaty of San Stefano. While Serbia gained recognition of its complete independence, Russia set up a massively enlarged Greater Bulgaria. This threatened the interests of Austria-Hungary and was generally unacceptable to the European powers, who did not want to see an expansion of Russian influence in the area. So in July of 1878 they called another conference, the Congress of Berlin.

While Serbian independence was maintained, the Congress of Berlin sharply restricted Russian aspirations and the Greater Bulgaria project was junked. Furthermore, Austria-Hungary was allowed to occupy Bosnia-Hercegovina. The reason was supposedly because the Turkish government couldn’t keep order. There was widespread opposition in Bosnia to the Austrian occupation, especially from the Moslems, and the Habsburgs had to bring in a large army to pacify the province. (Bosnia and Hercegovina were formally annexed by Austria in 1908.)

In the period leading up to World War I, the rivalries between the great powers and their respective clients in the Balkans increased, especially between Austria-Hungary, which sought an access to the Aegean Sea, and Turkey, and Serbia, backed by Russia and blocking this access.

In October 1912 the First Balkan War began. Bulgaria, Greece, Serbia, and Montenegro joined together and attacked Turkey. The Turks were defeated all along the line and lost almost all their European possessions.

The Second Balkan War began in the middle of 1913. It was a fight over the spoils of the first war. Serbia refused to share Macedonia with Bulgaria as agreed, and the Bulgarians attacked Serbia and Greece but were defeated.

The Serbian victories electrified the South Slavs in Austria-Hungary. They also dismayed the Habsburg regime, which saw Serbia blocking its road to the east. It determined to liquidate these “Guardians of the Gate”. The opportunity came when a Bosnian nationalist assassinated the Austrian Archduke Ferdinand at Sarajevo in June 1914. Austria used the incident to go to war against Serbia.

Trotsky’s view

At this point it is worth stepping back and considering the problem of the Balkans as a whole. Some comments by Trotsky from his Balkan journalism are very relevant here.

“The frontiers between the dwarf states of the Balkan Peninsula,” Trotsky wrote, “were not drawn in accordance with national conditions or national demands, but as a result of wars, diplomatic intrigues, and dynastic interests. The Great Powers — in the first place, Russia and Austria — have always had a direct interest in setting the Balkan peoples and states against each other and then, when they have weakened one another, subjecting them to their economic and political influence …

“The only way out of the national and state chaos and the bloody confusion of Balkan life is a union of all the peoples of the peninsula in a single economic and political entity, on the basis of national autonomy of the constituent parts …”

“State unity of the Balkan Peninsula,” he continued, “can be achieved in two ways: either from above, by expanding one Balkan state, whichever proves strongest, at the expense of weaker ones — this is the road of wars of extermination and oppression of weak nations, a road that consolidates monarchism and militarism; or from below, through the peoples themselves coming together — this is the road of revolution, the road that means overthrowing the Balkan dynasties and unfurling the banner of a Balkan federal republic.”[3]

But the postwar system of Balkan states was not based on the program of a Balkan federal republic advanced by the revolutionary social democracy. In fact, nowhere in Europe was the national question solved by the victorious Entente powers. Instead, the new Europe created by the Versailles and related peace treaties was based on a whole series of national injustices and contained the seeds of a new and more terrible world war.

The main aim of France and Britain in dismembering the defeated powers and redrawing the map of Europe was to create a system of states that would act as a barrier both to a German resurgence and to Soviet Russia.

As the “Manifesto of the Second World Congress” of the Comintern put it: “The new and tiny bourgeois states are only by-products of imperialism. In order to obtain temporary points of support imperialism creates a chain of small states, some openly oppressed, others officially protected while really remaining vassal states — Austria, Hungary, Poland, Yugoslavia, Bohemia, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Armenia, Georgia, and so on. Dominating over them with the aid of banks, railways, and coal monopolies, imperialism condemns them to intolerable economic and national hardships, to endless friction and bloody collisions.”[4]

The “Manifesto” went on to point out that “Virtually each one of the newly created ‘national’ states has an irredenta of its own, i.e., its own internal national ulcer”.[5] For example, three million Hungarians lived under foreign governments, German Austria was forbidden to unite with Germany, and Czechoslovakia contained a large German minority.

|

| Following World War I, the South Slav regions formerly ruled by Austria-Hungary were forcibly joined to Serbia in a centralised Yugoslavia. |

Formation of Yugoslavia

As World War I drew to a close, the main sentiment among the South Slavs of Austria-Hungary — the Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs — was for a union with Serbia and Montenegro in a Yugoslav (“South” Slav) state. During the war a Yugoslav committee representing the Austro-Hungarian South Slavs functioned in exile. It called for the unity of the South Slavs in an independent state.

By the end of 1918 Austria-Hungary was falling to pieces. The army was mutinous, and national feeling was running high in the southern Slav provinces.

On October 5 a National Council of the Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs was formed in Zagreb. Very rapidly it became the effective government in the South Slav areas of the empire.

On October 29 the Croat Sabor (Assembly) met and declared the union with Hungary to be ended and Croatia independent. It then voted to declare Croatia part of the sovereign state of the Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs (embracing Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia-Hercegovina, and the Vojvodina) and vested power in the National Council.

The National Council then undertook to unite the state of the Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs with Serbia and Montenegro. But the form of the union was not specified, and the Croat Peasant Party leader Stepan Radic opposed this proposal. He explained that the Croat masses were against centralism and militarism and were “for a republic no less than for a national agreement with the Serbs".[6]

There were quite clearly two roads open to achieve the unity of the Austro-Hungarian South Slavs with Serbia and Montenegro. One was the road of a Greater Serbia. This was the aim of the central Serbian political leader and Serb chauvinist Pasic, and also of Alexander, the Karageorgevic regent of Serbia. This project meant imposing Serbian hegemony over all the other areas and nations. It meant a unitary, centralistic state.

The other road was that of establishing a genuine federation of the various nations that would make up the new state. This would give each national grouping a wide degree of autonomy and self-government and would best accommodate the different historical, cultural, and socioeconomic levels of the various peoples.

An agreement reached on November 9 (the Geneva Declaration) agreed to form the new state but the governments at Zagreb (the state of the Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs) and Belgrade (Serbia) would remain until a constituent assembly had met and decided on a constitution for the whole country.

But in the event, on December 1, Alexander proclaimed the union of the two states into the Kingdom of the Serbs, the Croats, and the Slovenes. Montenegro joined shortly after. In violation of the previous agreement and in the spirit of the Greater Serbia project, the authority of the Serbian Belgrade regime was imposed on the rest of the new state.

Heavy opposition greeted the Serbian moves, and Serbian authority was imposed by force. French troops were also used in this operation. As a resolution of the First Congress of the Comintern noted, the Yugoslav government was “being established by armed force.”[7]

Thus, from the moment of its inception, bourgeois Yugoslavia (as the new state later became known) was built on Serbian oppression of the non-Serb peoples.

In November 1920, elections were held to form a constituent assembly to draft a constitution. In Croatia, the Croat Republican Peasant Party led by Stepan Radic won an overwhelming victory on a republican and federalist platform. Right through the 1920s and thirties, the CRPP (later the CPP) was the vehicle through which the mass of the Croat people attempted to realise their national aspirations.

One significant feature of the constituent assembly elections was the strong showing of the newly formed Communist Party. The CP emerged as the third strongest party in the country. Its 200,000 votes amounted to 12.4% of the total. In Macedonia it did even better — here it emerged as the strongest party, polling 40% of the votes.

In various municipal elections around the country in this period the CP also did very well. It had a majority in the Zagreb and Belgrade municipal administrations around this time.

But these successes and the rising wave of worker militancy alarmed the military and the big bourgeoisie. At the end of 1920 the party was banned. It had perhaps 60,000 members at this point.

After the November elections the CRPP boycotted the new assembly. Pasic and the Serbian parties pushed through a reactionary constitution. The constitution was adopted on June 28, 1921 — St Vitus Day, after which it is generally known. This constitution set up a centralist, monarchical state. It declared Yugoslavia to comprise one people of three different “tribes”. It ensured Serbian hegemony over the other nationalities and was strongly opposed by them.

|

| Stepan Radic, leader of the Croat Republican Peasant Party, assassinated in Yugoslav Parliament in 1928. |

The Comintern & the national question

The effort to hammer out the correct line on the national question was an ongoing one for the CP in the 1920s. It was also a central concern of the Comintern in its dealings with the Yugoslav party.

Early in 1923, for instance, the Executive Committee of the Comintern addressed a critical letter to the Communist Party. It stressed the need for the party to adopt the Leninist principle of supporting the right of oppressed peoples to self-determination, even to separate and form an independent state if they so wished.

The CP’s Third Conference, held illegally in Belgrade at the end of 1923, reflected this pressure. Its “Resolution on the National Question” stated that Yugoslavia was not a “homogeneous nation state with certain national minorities but rather is a state in which the ruling class of one (the Serbian) nation is oppressing the other nations.”[8]

In mid-1924 the Fifth Congress of the Comintern was held. It adopted a resolution on the national question in Yugoslavia and the Balkans. And although this congress was held in a period when the process of degeneration of the Russian Revolution and the Comintern was already well under way, that does not at all mean that its resolutions are uniformly worthless. Certainly this particular resolution is firmly in the Leninist tradition.

The resolution noted that in Yugoslavia the Serbian bourgeoisie was subjecting the other peoples to a regime of national oppression and forcible denationalisation. It pointed out that the theory of “a united trinity of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes is only a mask for Serbian imperialism”.

The Communist Party had to “fight for the self-determination of the different nations, to support the national liberation movements, constantly to strive to remove these movements from the influence of the bourgeoisie and connect them with the common fight of the working masses against the bourgeoisie and capitalism.”

The resolution went on to note that in Yugoslavia there was a mass movement against national oppression. In view of this, “the general slogan of the right of nations to self-determination, launched by the Communist Party of Yugoslavia, must be expressed in the form of separating Croatia, Slovenia, and Macedonia from Yugoslavia and creating independent republics of them.”[9]

So, at this point, because of the strong national movements, the Comintern favored the slogan of separation.

Early in 1925, at a meeting of the ECCI’s Yugoslav commission, Stalin debated Sima Markovic, a central leader of the CP. Stalin correctly pointed out that supporting the right of a given nation to selfdetermination, to secede if it wished, in no way meant an obligation to secede. And if a nation chose to remain in the existing state, then it should receive a wide regional autonomy.

Royal dictatorship

The decade of the 1920s saw no solution of the national problem in Yugoslavia. In August 1924 Pasic jailed Radic and attempted to dissolve the CRPP. But these measures led to an even stronger showing by the CRPP in the February 1925 elections. Pasic made a deal, released Radic, and Pasic’s Radical Party and the CPP (the “Republican” was dropped) formed the new government in the middle of the year.

By 1927 Radic was back in opposition, demanding a federal reorganisation of the state. On June 28, 1928, Radic was shot in the Belgrade parliament by a Serb chauvinist. He died shortly after. The country went into a fundamental crisis of the whole system. There were two opposed camps — Belgrade and Zagreb. The Croats and other opposition forces began to organise a counter-government at Zagreb. The Belgrade coalition government collapsed. The whole Yugoslav political system had broken down.

Something had to give. The king, Alexander, even explored the possibility of “amputating” Croatia and Slovenia, but the idea received no support. On January 26, 1929, Alexander carried out a coup d’etat, dissolving the parliament and abolishing the 1921 Constitution. The regime passed a law for the defence of the state that provided harsh penalties for terrorism, sedition, communist propaganda, and so on. The centralist, Serbian-dominated orientation of Belgrade remained as before. All opposition was repressed.

|

| Ante Pavelic, founder and leader of the rightist, nationalist-terrorist Ustasha organisation, |

It was at this point that the Croatian leader Ante Pavelic fled abroad and established the separatistterrorist Ustasha organisation. (The name means “arise” and refers to Croat rebels of the past.) It was agents of Pavelic who assassinated Alexander in Marseilles in 1934.

In an effort to resolve the ongoing Croatian national problem, which continually undermined the foundations of the whole state, the regent, Paul, concluded an agreement, the Sporazum, with the CPP leader Vlatko Macek in August 1939. This provided for a province of Croatia, with a certain measure of autonomy being exercised by an assembly at Zagreb.

On the basis of this agreement, a new government was formed, the Cvetkovic-Macek government. (Macek was vice-premier.) While the CPP accepted the agreement, Pavelic and other separatists opposed it. It was also strongly opposed by many Serbian chauvinist elements, who saw it as a sell-out of Serb domination.

World War II

On March 25, 1941, Yugoslavia adhered to the Tripartite Pact, the alliance between Germany, Italy, and Japan. For Hitler, this was one of the essential preliminary moves for his planned assault on the Soviet Union.

The day after signing the pact, the Belgrade regime was toppled by a coup d’etat. The coup was the work of pro-Allied Serb officers, politicians, and priests, who were not only opposed to the Axis alliance but were also opposed to the regime for the compromise it had negotiated with the Croats. They wanted to ensure the survival of the Serb-dominated, centralist system.

Hitler reacted to the coup by invading Yugoslavia on April 6, 1941. The Yugoslav forces disintegrated rapidly and by April 17 the army had surrendered. One important reason for Hitler’s quick victory was the continuing national disaffection, which undermined the will of the Yugoslav army to fight.

In his attack on Yugoslavia, Hitler’s propaganda, as in previous campaigns, sought to exploit the national question. In fact, in his rise to power and subsequent European hegemony, Hitler always sought to portray himself as the liberator of the peoples oppressed by the unjust Versailles system. Of course, this was just a mask for the predatory plans of German imperialism.

In Yugoslavia, the victorious Axis powers partitioned the country and established a harsh regime. The biggest fragment of dismembered Yugoslavia was the so-called Independent State of Croatia, or NDH from its Croat initials. The NDH was proclaimed on April 10, 1941, and a government set up under Ante Pavelic and resting on the Ustasha. Appearing to many Croats as the realisation of national goals so long fought for, the NDH at first enjoyed considerable support.

But, established in the midst of the German invasion, the NDH from the outset was completely subordinated to German and Italian imperialism. The Italians seized the Dalmatian coast and as well had an extensive sphere of interest. German troops occupied all the major towns outside of the Italian zone.

Furthermore, Pavelic’s regime carried out extensive repressions, pogroms, and atrocities, against its enemies — the Serbs, Jews, and supporters of the Partisans. While these crimes, terrible enough, appear to have subsequently been exaggerated considerably — see below — they did take place, and on a wide scale, and were, in fact, inevitable given the right-wing bourgeois orientation of the Ustasha leadership.

It is important for Marxists to be clear on the question of the NDH and the Ustasha. I think the HDP is completely correct when they deny that the Ustasha was fascist. In the scientific, Marxist sense of the term, it was not. It began as a right-wing nationalist-terrorist organisation seeking Croatian separation from Yugoslavia.

Much is made of its links to Italian imperialism in the prewar period. But we must be precise here. There is nothing wrong with a national liberation movement taking aid from wherever it can find it. The Irish freedom fighters accepted German aid in World War 1. Were they wrong in doing this? We don’t think so. The Germans had their own reasons for aiding the Irish — to embarrass the British. The Irish accepted this aid and used it to continue their fight for a free and united Ireland.

Again, we do not criticise a national movement for attempting to exploit the antagonisms between the imperialist camps in order to seize independence from the oppressor state. Croatia owed nothing to the Belgrade regime of the Serbian bourgeoisie. It certainly owed nothing to the Allied imperialist camp.

Pavelic betrayed the Croatian national movement, not because he took aid from one gang of imperialists, not because he declared independence in the midst of a war between two imperialist gangs. He betrayed because he subordinated the Croatian national struggle to imperialism, in the given case to German and Italian imperialism.

It was because of this that the NDH could in no way bring real freedom to the mass of the people or establish anything but a mockery of independence. The Europe set up by the Allies at Versailles was built on national oppression and injustice, but Hitler’s new European order was no less erected on oppression of the peoples. Real national liberation can be won only in a process of implacable struggle against imperialism, of whatever stripe.

It is hard to avoid the conclusion that much of the motivation for labeling the NDH and the Ustasha as fascist is the desire to discredit the whole idea of the Croatian national struggle then and now. One argument used by implication is that the scale and nature of the crimes of the NDH regime show its fascist nature. But in the period of capitalist decline all the forms of imperialism assume a barbarous character. It was the regime of US “democratic” imperialism that unleashed the atomic bombs on Japan. Fascism has no monopoly on horror.

Two other movements contended for supremacy in Yugoslavia during the war. These were the Chetniks and the Partisans.

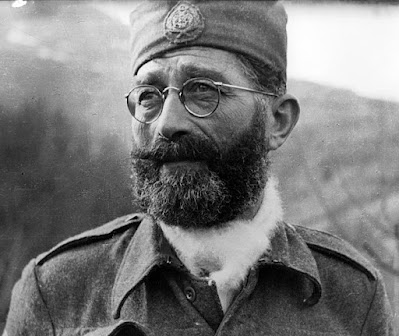

|

| Serb Chetnik leader Draza Mihailovic. |

The Chetniks were led by Draza Mihailovic, a colonel in the Yugoslav army. (The name comes from the Serb bands that fought the Turks in earlier times.) Mihailovic and the Chetniks had a Serb-chauvinist, monarchist outlook. As one conservative account of this period puts it: Mihailovic “was a Serb and always put Serbian interests (as he saw them) first; he was continuously aware of his duties as an officer and his responsibilities to his king.”[10] Mihailovic was opposed to both the Croats and the Communists. For a period (January 1942 to May 1944) Mihailovic was minister of defence in the royal government-in-exile.

The Chetniks remained largely composed of Serbs. Their narrow Serb outlook meant they had no appeal for any of the other nationalities. Furthermore, after some initial opposition to the German occupiers, they soon gave this up. Mihailovic wanted to preserve his forces until the Germans were weaker and then use them to impose order and restore the monarchy and the Serbian-dominated, centralised state.

The Chetniks’ main efforts went into fighting the Communist-led Partisans. In Serbia the Chetniks had an arrangement with the puppet regime there whereby it controlled the towns and the Chetniks controlled the countryside. Chetnik domination of Serbia remained until near the end of the war, when the Partisans were finally able to defeat them.

Following the German invasion of the Soviet Union in the middle of 1941, the Communist Party issued a call for a general uprising and began to organise the Partisan army. Over the course of the war, this grew into a massive movement, which waged a heroic struggle against the occupiers and their local collaborators. Hundreds of thousands fell in this struggle.

The Partisan movement became the vehicle for a social revolution and carried the hopes of the people for a new, free Yugoslavia to be created after the war. The Partisan movement gave rise to a body known as the Anti-Fascist Council for the National Liberation of Yugoslavia (AVNOJ), which effectively functioned as a provisional government.

The AVNOJ first met in November 1942 in Bihacs in Croatia. A second session was held at Jajce in Bosnia a year later. The Jajce assembly set up a provisional government with Tito as premier. It proclaimed that the new Yugoslavia would be set up on a democratic and federal basis. It also warned the king not to return, as the question of the monarchy would be decided by the people after the war.

The national program put forward by the Anti-Fascist Council was decisive in enabling the Partisan movement to win the support of the masses of the non-Serbian nations. The Chetniks’ unitarist, Serb-chauvinist, and monarchist outlook could not attract the non-Serb peoples; indeed it seemed to promise even harsher national oppression than had existed before the war. Also, with the withdrawal of Allied support and the waning of the Axis fortunes, the Chetniks’ prospects looked more and more bleak.

As for the NDH, its appeal as a lasting solution to the national aspirations of the Croat people was rapidly undermined by its territorial concessions to the Italians, its complete subservience to the Germans, and its reign of terror against all opponents. As the tide turned against the Axis powers, the future of the NDH seemed very limited. The support of the Croats for the Partisan movement gradually increased. This was helped by the proclamation of a Croatian state within a new Yugoslav federation even during the war.

Yugoslav workers state

At a meeting in Moscow late in 1944, Churchill and Stalin came to an agreement on the respective British and Soviet spheres of influence in the Balkans. Romania, Bulgaria, and Hungary were assigned to the Soviet sphere, Greece to the British, and in Yugoslavia each was to have a half share.

Under great pressure from the Allies, Tito agreed to form a coalition government with some bourgeois, monarchist elements. This was set up in March of 1945. Ivan Subasic, prime minister of the royal government-in-exile, became foreign minister in the short-lived “United Government”.

But despite the Allied pressure for concessions, there was never any real compromise with the royalists. Subasic and his colleagues had no real base of support among the people. This government ended with Subasic’s resignation later in the year.

In the elections to the federal parliament held on November 11, 1945, the CP-led People’s Front scored a massive victory. reflecting their wartime record and popular support.

Through the policy, begun during the war, of confiscating the property of collabourators, and through further nationalisations in 1945, the new government already controlled the bulk of industry. State ownership of industry and intervention in all spheres of economic lite deepened over the next year. leading to the creation of a workers state.

The new parliament met on November 29, 1945, and proclaimed the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia. The new constitution, adopted in the following.lanuary, defined the new state as a federal union of national republics. Each republic was guaranteed the right to self-determination, including the right to secede.

|

| Franjo Tudjman, Partisan general, postwar leader and later Croat dissident. |

Postwar period

In the section which follows on postwar Yugoslavia, I’ve drawn fairly heavily on a book by Franjo Tudjman called Nationalism in Contemporary Europe.[11]

Tudjman is a well-known Croatian writer and historian. During the war he was one of the youngest Partisan generals and a leader of the Partisan forces in northern Croatia. In 1981, Tudjman was tried by the Yugoslav authorities on fabricated charges. He received a three-year jail sentence and a five-year ban on any public expression. His case is mentioned in the Amnesty International report on Yugoslavia that was published last year.

While Tudjman’s view of Marxism has obviously been distorted by the fact that it is the proclaimed ideology of all the Stalinist regimes in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, his book is a very serious and thoughtful work, from which we can learn a great deal.

The establishment of the Federal Republic and the creation of the Yugoslav workers state were great advances for the toiling masses of all the Yugoslav nations. These two developments were essential preconditions for a real and lasting solution of the national problem in Yugoslavia. In view of the many problems that have since developed in this regard, it is worth briefly listing some of the key gains made by the formerly oppressed nations.

Croatia received its national statehood in the federal order, and certain Croat lands some of the Adriatic islands and the Istrian peninsula below Trieste were liberated from Italy.

Slovenia gained statehood for the first time ever, and some Slovene lands formerly under Italy were treed. Macedonia gained statehood for the first time in history under the federal system; Macedonian was declared the official language for the first time. For the first time since 1918, Montenegro regained a separate national status. And the autonomy gained by Kosovo and Vojvodina, despite its limitations, has meant great progress for the Albanian and Hungarian national minorities as compared to their prewar situation.

However, the national problem has not been solved in Yugoslavia. National oppression still exists. There developed a massive contradiction between the socialist principles proclaimed in the Constitution and the actual practice of the Communist Party leadership of Yugoslavia.

The essential reason for this has been that the reality of bureaucratic domination, which is necessarily centralised, negates in practice the forms of federal decentralisation on which the state is nominally based.

As Franjo Tudjman puts it, “despite the federal state structure, a totally centralistic system was constructed with huge administrative federal bodies for all spheres of social life, from politics and economics to culture and sport. Complete authority was in the hands of the federal organs while the republics were reduced to executive organs of the federation … [And] because all political and administrative authority and economic and financial power was concentrated in Belgrade and also because the Serbs were the most numerous nation and nurtured a traditional distrust towards the other nationalities (primarily the Croats) … the Serbian element gradually became dominant, particularly taking over the most sensitive sectors and key positions, not only in the federal administration but also the republics and provinces.”[12]

This description applies to the state structure as it was built up after the war and in the 1950s and early sixties. Various reforms have changed aspects of this picture but not the reality of Serbian domination of the state. In 1963, a new constitution was promulgated that strengthened the federal system in the political sphere but which did not alter the system of allocating economic resources, a vitally important question in a genuine federation.

In 1966 a plenum of the Central Committee of the League of Yugoslav Communists (as the CP is formally named) was held at Brioni in the Adriatic. Alexander Rankovic, vice-president of the republic and head of state security, was dismissed from all his official positions.

He was accused of repressing the Albanian minority in Kosovo and of running a secret network within the security services. Rankovic was made the scapegoat for the heavy system of Stalinist repression that existed. In Croatia, for instance, the police kept files on 1.3 million people — about two-thirds of the entire active population.

The decisions of the Brioni plenum heralded a stepping away from the extremely centralist practices hitherto carried out and a move towards a real reform of the federal system as well as a move towards a general democratisation.

|

| Savka Dabcevic-Kucar, President of the Croatian League of Communists and Prime Minister of Croatia, was one of the leaders of the Croatian Spring (1968-71). |

A widespread liberalisation developed, driven forward by a growing mass movement, especially in Croatia. This process developed most tumultuously in the period from 1968 to 1971. The mass reform movement of those years has been termed the “Croatian Spring,” and in fact it was inspired and stimulated by the reform movement in Czechoslovakia — the “Prague Spring” — which developed in 1967-68, and with which the Croatian movement had many similarities.

One aspect of this process was a certain democratisation of the party. For the first time in the history of the LCY, in 1968 congresses of the various republican parties were held prior to the federal congress in 1969. The election processes were democratised, and there were radical changes in the composition of many leading bodies, with new, younger leaders coming forward.

For the first time, the republican congresses themselves selected their representatives to the leading bodies of the LCY, and these bodies were constructed on a parity basis (equal representation from the various republics, etc.). Thus, as Tudjman puts it, “a kind of federalisation of the LCY was carried out.” This in turn stimulated the campaign for further reforms.

In this period a series of political and constitutional reforms were set in motion through which the federal character of the Yugoslav state was much more clearly defined. The Council of Nations was set up as the most important council in the Federal Assembly. The Federal Executive Council (the government) was constituted on a parity basis as regards republican representation. The self-government rights of the republics were strengthened.

But on the level of economic decision-making and the economic relations between the federation and the republics, the changes were much less fundamental.

The gains and reforms won by the mass movement stimulated the demand for further and more far-reaching changes. From the point of view of the central bureacratic leadership, certain reforms and concessions had to be made in order to preserve the Yugoslav state. The Soviet crackdown in Czechoslovakia in 1968 played an important role in impelling the leadership to make certain reforms in the federal system in order to strengthen the country.

The mass movement in Croatia was led by reform elements in the leadership of the Croatian party. Tudjman explains that “Croatia was swept by a democratic revival movement which was set in motion by the intelligentsia, but which was joined by all the other strata from students to workers and peasants, and even the majority of the League of Communists. The political and state leadership of the League of Communists of Croatia and the Socialist Republic of Croatia itself stood at the head of this movement especially following the historical Xth session of the Central Committee of the League of Communists of Croatia (January 1970) when the ideology of Yugoslav unitarianism was condemned as the dominant and persistent political tendency preventing the equality of the Croatian nation and endangering the stability and further social development of Yugoslavia.”[13]

Tudjman goes on to point out that “the younger generation of party leaders, who supported the democratic-liberal reforms of the federation, and who had consequently won massive popularity especially in their own republics (Miko Tripalo and Savka Dabcevic-Kucar in Croatia …) were politicians of the new mould, with more modern and dynamic views, who within the context of international and internal developments began to seek a way out of the crisis of the totalitarian-socialist society in its democratization and humanization. This led them to establish close links with the intelligentsia and the masses of the people.”[14]

One striking example of this came in May 1971, when a huge mass rally was held in Zagreb. Several hundred thousand people turned out. It was the biggest meeting in Croatia in the postwar period. It was addressed by Savka Dabcevic-Kucar, president of the Central Committee of the League of Communists of Croatia. One writer described the rally as “a triumph of Croatian national feelings and aspirations for freedom, sovereignty and national equality.”[15]

The reform process was brutally terminated at the December 1, 1971, meeting of the Presidium of the LCY Central Committee at Karadjordjevo. Tito initiated a sweeping purge of the Croatian reform movement in all its aspects. The party and state leadership were purged; the most prominent figures in the Matica Hrvatska (Croat Headquarters-a famous Croatian cultural institution) along with leaders of the student movement were jailed; and thousands of people in all areas of social life were arrested, sacked from their jobs, or persecuted by the police. One estimate is that as many as 32,000 people in Croatia were affected in one way or another by Tito’s crackdown.

The crackdown extended to supporters of the reform process in the other republics, but although the purges here were extensive they were not as brutal as in Croatia.

The repression showed that Tito felt the reform movement was beginning to undermine the whole basis of bureaucratic rule in Yugoslavia. “By the end of 1972,” Franjo Tudjman writes, “Yugoslavia was once again a socialist country where all the reins of power and control over all aspects of socio-political activities were in the hands of the ruling group within the LCY supported by Tito’s authority.”[16]

However, when the new constitution of 1974 was promulgated, the reforms of the federation initiated in 1968-71 were preserved. The right to self-determination, including the right to secession, appears as always.

But despite this, in Yugoslavia today there is a glaring contradiction in the national sphere between the promises made in the constitution and the practice of centralist bureaucratic rule.

|

| Josip Broz Tito, dominating figure in wartime Partisan struggle and postwar Yugoslavia. |

Oppressed nation

The reality of the national oppression of the Croatian people in Yugoslavia by the Serbian-dominated system can be seen vividly with the help of a few statistics cited in Franjo Tudjman’s book.

- In a multinational workers state in which the Communist Party is the sole legal party, the latter’s national composition reflects the relations between the various nations. In 1946 the League of Communists of Croatia accounted for almost 31% of the total membership of the LCY. This was about 8% more than Croatia’s share in the total population of Yugoslavia and reflected the strength and weight of party organisation in Croatia and the role played by the population (both Croat and Serb) in the wartime struggle. But by 1978 this figure had fallen to 17%, well below Croatia’s percentage of the overall population (about 22%). This shows the distrust of the ruling layers towards the Croats as well as Croatians’ growing lack of confidence and interest in the party.

- In Croatia in 1978, one in four Yugoslavs (that is, Montenegrins, Macedonians etc) belongs to the League of Croatian Communists, one in nine Serbs, but only one in 20 Croats! And in Bosnia-Hercegovina, the other republic with a large Croat population, we find even more disproportionate figures: One in five Yugoslavs belongs to the party, one in 11 Serbs, one in 16 Moslems, but one in 25 Croats!

- The officer cadre of the Yugoslav People’s Army consisted, in 1978, of only 15% Croats. At the end of the war, it appears that this figure was well above the percentage of Croats in the population.

- In 1969 figures for the national composition of the major institutions of the federal administration were made public. There was public consternation when these showed 73.6% Serbs and only 8.6% Croats. By 1978, the proportion of Croats had fallen to 6%. That is, just under 40% of the population is Serb but Serbs make up almost three-quarters of the staff of the federal institutions!

- Another example is the role played by Serbs in the League of Croatian Communists. In Croatia almost 80% of the population are Croats and only 14.2% Serb. Yet in the LCC and in the state leadership, Serbs hold a large percentage of key positions.

- In 1971, 51% of the 1.2 million Yugoslavs temporarily employed in Europe were Croats and another 20% were Moslems.

Another index of Croatia’s national oppression in Yugoslavia is to be found in the allocation of the social product. (The following figures are taken from the pamphlet by Marko Veselica.)

In the decade of the 1960s, for example, Croatia created 27% of the national income, yet received only 11% of new investments. In the same period, Serbia created 33% of the national income of the country yet received 60% of the new investments.

In this period, Croatia earned about 50% of Yugoslavia’s foreign exchange yet disposed of only 11% of it. At the same time, Serbia earned less than 25% of the country’s foreign exchange, yet it disposed of over 80% of it. Yugoslavia has a somewhat different economic system than the other workers states, but that does not really affect this argument.

Franjo Tudjman writes that at one point, so much wealth was being taken out of Croatia, so high a proportion of the national income of the republic, that not even simple reproduction of the economy was possible!

One of the demands of the reform movement in the late 1960s was the transfer from Belgrade back to the republics of control over new investments.

It could be argued that this is a retrograde step and that the federation takes wealth produced in the richer areas and allocates it to building up the poorer regions. Before dealing with this claim, perhaps it is useful to look at the per capita income levels of the various republics and provinces. These certainly show that Yugoslavia embraces vast disparities in levels of development.

In 1979, according to official figures, the per capita annual income in Slovenia was $4000, in Croatia $2400, in Vojvodina $2100, in Serbia proper $1800, in Bosnia-Hercegovina and Macedonia $1300, in Montenegro $1200, and in Kosovo $500.[17]

One point to consider, however, when looking at the Croatian figure is that half a million Croats have been forced to look for work in Western Europe. If they all returned home, 40% of the workforce would be unemployed, and the per capita annual income would fall below the national average.

However, the wealth that is transferred from Croatia doesn’t in the main go to the poorer regions but to Serbia. And then again, the bureaucracy squanders, on itself, a large part of the national income.

Trotsky dealt with this latter point in his Ukrainian articles. He wrote that “it is impermissible to forget that the plunder and arbitrary rule of the bureaucracy constitute an important integral part of the current economic plan, and exact a heavy toll from the Ukraine.”[18]

In the case of Yugoslavia, not only does the bureaucracy gobble up a large amount of the country’s income, but its incompetence and mismanagement of the economy have created a debt to theforeign banks second only to Poland’s in Eastern Europe. Even the funds that are committed to the poorer regions do not necessarily do much good there, given the bureaucratic administration. All this is justifiably resented by the Croatians.

Internationalist aid, such as revolutionary Cuba extends to many Third World countries, is very important. But it must be voluntary, it must result from the free decision of the people concerned. The Croatian people must be masters in their own house and be able to set about overcoming the many problems they face. Then they will consider freely a new relationship with their poorer neighbors.

One other aspect of the national oppression experienced by the Croatian people concerns the attempts to fasten on them an idea of “collective guilt” for the wartime Ustasha crimes. This is a conscious mechanism of the bureaucracy, similar in some ways to the liberal idea that the German people bear a “burden of guilt” for Hitler and fascism.

Part of this campaign involves branding nationalist activity as fascist and linked to the Ustasha. Franjo Tudjman presents evidence that the scale of the Ustasha crimes — real enough and horrifying enough as they were — have been exaggerated wildly, even as much as 10 or 12 times.[19]

The object of this campaign by the regime is, as Tudjman puts it, “that of imposing on the Croatian nation the feeling that it does not have any right to protest but only atonement, regardless of the things which have happened to it.”

“Moreover,” Tudjman continues, “the dissemination of the theory of the enormous historical guilt of the Croatian nation also serves to cover up the truth that in World War II Croatia was not only on the side of the Axis Powers but was also one of the firmest footholds of the anti-fascist movement, giving not a smaller but larger contribution in blood to the victory of the democratic forces over fascism than the other Yugoslav nations.”

Example of the Russian Revolution

At this point I want to step back a little and place the Croatian struggle in a broader framework. What role does such a national struggle play in the political revolution against the bureaucracy in a Stalinised workers state?

For the correct Marxist handling of the national question in a workers state, the experiences of the Soviet Union in its early years, when it was led by Lenin and Trotsky, remain for us a model.

In 1922, a struggle broke out in the Bolshevik Party around the formal establishment of the USSR. Stalin at first proposed to have the new state set up by the independent socialist republics of the Ukraine, Transcaucasia, etc joining the RSFSR — the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic — as autonomous provinces. Lenin sharply opposed this, insisting that the RSFSR and the other republics should come together as equals in a new union.

Stalin’s plan reflected a Great Russian chauvinistic attitude. Historically, the Russians had been the dominant nationality, on which the tsarist empire had been based. Russian chauvinism towards the nonRussian nations had a long historical tradition. It was vital for the revolutionary leadership, the Communist Party, to combat any and all manifestations of this reactionary outlook, especially inside the party.

In the event, Lenin’s ideas won out, and on December 30, 1922, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics was established. Each republic in the union had the right to self-determination, including the right to secede from the union if it wished.

Lenin’s testamentary writings on the national question in the workers state contain priceless guidelines for revolutionaries.

Lenin stressed that “an abstract presentation of the question of nationalism in general is of no use at all. A distinction must necessarily be made between the nationalism of an oppressor nation and that of an oppressed nation, the nationalism of a big nation and that of a small nation.

“In respect of the second kind of nationalism we, nationals of a big nation, have nearly always been guilty, in historic practice, of an infinite number of cases of violence …

“That is why internationalism on the part of the oppressors … must consist not only in the observance of the formal equality of nations but even in an inequality of the oppressor nation, the great nation, that must make up for the inequality which obtains in actual practice. Anybody who does not understand this has not grasped the real proletarian attitude to the national question …

Lenin continued: “What is important for the proletarian? For the proletarian it is not only important, it is absolutely essential that he should be assured that the non-Russians place the greatest possible trust in the proletarian class struggle. What is needed to ensure this’? Not mere formal equality. In one way or another, by one’s attitude or by concessions, it is necessary to compensate the non-Russians for the lack of trust, for the suspicion and the insults to which the government of the ‘dominant’ nation subjected them in the past …

… nothing holds up the development and strengthening of proletarian class solidarity so much as national injustice … That is why in this case it is better to overdo rather than underdo the concessions and leniency towards the national minorities.”[20]

Trotsky on the Ukraine

As we know, the national program of the Bolsheviks in the USSR was trampled into the mud by Stalin and the Great Russian bureaucracy. Just as class antagonisms and social inequality did not wither away in the Soviet Union, neither did national inequality and oppression. In fact, it intensified.

What this means for us today is that in the bureaucratised workers states the program of the political revolution must include demands on the national question. Trotsky’s articles on the Ukraine, written just before World War 1II, provide invaluable guidance for us.

Trotsky pointed out that “The federated structure of the Soviet Republic represents a compromise between the centralist requirements of planned economy and the decentralist requirements of the development of nations oppressed in the past.”[21]

Furthermore, Trotsky explained, the establishment of the federal union didn’t settle the national question in the USSR for all time. Depending on the actual developments in the case of a given nation, it might be satisfied with the federation or it might wish to withdraw and form a separate state. That is why the Soviet Constitution guaranteed the right of self-determination to each nation. (Also, the very act of including the right to national self-determination in the Constitution was a pledge by the state to do all in its power to make the federation work as a free and equal union.)

The correct political approach for Marxists when confronted by national injustice is not to engage in “sterile speculation on the superiority of the socialist unification of nations as against their remaining divided.”[22] Rather, it is to ascertain “whether or not a particular nationality has, on the basis of her own experience, found it advantageous to adhere to a given state.”[23]

And in the case of the Ukraine, there had been a “massacre of national hopes”, Trotsky wrote.[24]

“The great masses of the Ukrainian people are dissatisfied with their national fate and wish to change it drastically. It is this fact that the revolutionary politician must, in contrast to the bureaucrat and the sectarian, take as his point of departure.”[25]

This is the decisive point in Trotsky’s writings on this question. We are revolutionary politicians. We take reality as it is, not as we would like it to be. We go to the masses where they are and as they are and formulate a transitional program to mobilise them in struggle and lead them forward and raise their consciousness.

Trotsky contrasted the revolutionary approach to the nationally oppressed Ukrainians to that of the Kremlin bureaucracy.

The bureaucrat says: “inasmuch as the socialist revolution has solved the national question, it is your duty to be happy in the USSR and to renounce all thought of separation (or face the firing squad). By contrast, the revolutionist says: “Of importance to me is your attitude toward your national destiny and not the ‘socialistic’ sophistries of the Kremlin police; I will support your struggle for independence with all my might!”[26]

If revolutionists do not fight for the leadership of the national movement in the bureaucratised workers state, if they do not have a program that will enable them to do this, then the masses of the oppressed nation will fall under the leadership of rightist, pro-imperialist elements, who will lead them into disaster.

In his articles, Trotsky took up and answered a number of arguments raised against his slogan of an independent Soviet Ukraine.

First, there was the argument I have already mentioned. That is, it is more advantageous “in general” for various nationalities to live together in the framework of a single workers state than to exist separately. The problem with this approach is that it does not deal with the actual sentiments and mood of the masses of the given nation.

What if the nation is oppressed and wants to leave the state? Do we oppose its aspirations and lecture it on the virtues of a socialist federation? Or do we intervene by championing the national aspirations of the oppressed people, thereby enabling us to win them to the struggle for socialism rather than have the national movement fall under reactionary leadership?

Another argument against an independent Soviet Ukraine took the line that with the removal of an important economic entity such as the Ukraine, the economic plan would be disrupted and the development of the productive forces of the USSR would be set back. But, Trotsky, answered, a plan is not sacred. If the Ukraine wants to separate, this means that the plan does not satisfy it. The plan can be reworked to take account of the separation of the Ukraine, and if the new plan were advantageous to the Ukraine, then it would be able to reach an agreement with the USSR.

Then, what about the dangers to the Soviet Union if the Ukraine seceded? Wouldn’t the USSR be militarily weakened and mightn’t imperialism attempt to take advantage of this? Trotsky answered that it is true that there are certain risks involved. But then there are risks entailed in the fight for the anti-bureaucratic revolution as a whole. But it is certain that if the bureaucracy is left in control, then the Soviet Union is doomed anyway. In order to defend the workers state, the bureaucracy must be removed. The national uprising is only a segment of the political revolution. And an independent Soviet Ukraine would, out of self-interest, be compelled to enter into a military agreement with the Soviet Union.

The other aspect of this matter was that unless the Ukrainian national question could be solved, then “in the event of war the hatred of the masses for the ruling clique can lead to the collapse of all the social conquests of October.”[27] This tendency was seen in the Ukraine in 1941, when Hitler invaded. Large numbers of Ukrainians welcomed Hitler as a liberator at first. This attitude changed when harsh experience convinced them of his real intentions — to dismantle the real gains of October and enslave and exterminate them.

The case of Croatia

While there are some obvious differences between the situation of the Ukraine on the eve of World War II and that of Croatia today — in the nature of Yugoslavia compared to the Soviet Union, in the geopolitical situation, and so on — we can apply Trotsky’s method, his political approach, to the case of Croatia. The key question is a political one: How should Marxists relate to the Croatian national movement in order to lead it forward along the path of socialism?

Our approach consists, in the first place, in supporting the right of the Croatian nation to self-determination. including the right to leave Yugoslavia and form an independent state.

Do the majority of the Croatian people want a separate state? Or is the direction of their struggle to radically restructure the Yugoslav federation and make it honor its promises in reality? It is difficult for us to answer this question without more factual information. Quite possibly the desire to separate is the majority sentiment.

In any case, this is not the key question for us as Australian revolutionaries. The principled position we must take is to support the right of the Croatian people to freely decide their national destiny. If they want to leave Yugoslavia, we support that decision and will help them fight for the new state. If they wish to remain and restructure the federation, we shall support them in that case also.

But whatever the case, we can and shall collaborate closely with a nationalist separatist organisation such as the HDP.

Of course, in discussing the Croatian national struggle in general, or the question of Croatia’s separation from Yugoslavia, a great many concrete problems and aspects of the matter could be raised. We can’t deal with all these here. But I’ve tried to indicate both our principled line and the method, the political approach, that we must apply to this problem.

Collaboration with the HDP

In the final part of this report, I would like to make some comments about the developing collaboration between the Socialist Workers Party and the Croatian Movement for Statehood.

This collaboration is based on two considerations. First, there is the SWP’s firm support for the struggle of the Croatian people for national justice. We support their right to national self-determination in Yugoslavia, up to and including the right to secede and form an independent state if they wish.

The second consideration is the progressive positions taken’ by the HDP and its continuing positive evolution.

This collaboration has certainly been a two-way street. We have learned a lot from it so far and will undoubtedly learn a lot more. We’ve definitely learned a lot about the history and politics of the Balkans and, in retrospect, the publishing of Trotsky’s book (The Balkan Wars) several years ago was certainly well timed.

We have gained a much more concrete understanding of the nature of the system of bureaucratic rule in Yugoslavia. We’ve been forced to think a lot more about the political revolution in a country like Yugoslavia and how the struggle against national oppression fits into this. We have also gained a real education on the richness and historical legitimacy of the Croatian national tradition and struggle and have been forced to confront some of the stereotyped images of this struggle, which had affected us along with the rest of the left in Australia. All this has been an extremely positive experience.

On the other hand, we’re confident that in the process of common work and discussion with the HDP, we can demonstrate the validity of Marxist ideas and show that these have nothing to do with the bureaucratic falsifications of Marxism promulgated by Belgrade and Moscow.

Furthermore, our work with the HDP can help to strengthen the party’s work in the labour movement in this country. Around 200,000 Croatians live in Australia, and the vast majority of these belong to the working class. Many work in the building trades. While some Croats will return to Croatia someday, the great majority will stay and live and work here. Through the HDP we can gain their attention and carry on party work among them, especially our industrial and trade union work.

Since its formation in 1981, the HDP has taken some very progressive stands. The articles by Jamie Doughney and Jim Mcllroy in the October 5 and October 20 issues of Direct Action last year give an extensive account of these. But it’s worth recalling them briefly because quite a few supposedly left-wing groups don’t perform nearly as well:

- The HDP supports the Irish freedom struggle and has carried material on this in Croatian Weekly.

- During the Malvinas war, the HDP came out against British imperialism and for Argentina.

- The HDP supports the revolutionary processes in Nicaragua and El Salvador, and HDP comrades are active in Central America solidarity work in Melbourne.

- The HDP supports the Palestinians in their struggle against Zionism and imperialism.

- And, as the Direct Action series pointed out, many HDP members identify strongly with Fidel Castro and revolutionary Cuba; Che Guevara remains a revolutionary symbol for them also.

Through its ongoing struggle, the HDP has established itself as the most influential group in the Australian Croatian community. The Croatian Weekly is certainly the most widely read Croatian-language paper in Australia.

The HDP’s efforts to get itself established in the Croatian community have meant an ongoing confrontation with right-wing elements. H DP members have been bashed and even knifed by rightist thugs. But the HDP’s efforts have more and more isolated the right-wing elements. Support for the HDP’s general orientation has grown considerably.

In the postwar period, and even into the early 1970s, there was a strong tradition of Croatian community support for the Liberal Party. That is a thing of the past. A sign of the new reality is the Croatian Weekly’s support for Labor in the last elections.

The HDP, of course, is a coalition of views. That’s true internationally as well. And on the international level, the Australian HDP is on the left wing. The example of the Australian HDP has already had a strong influence on the HDP abroad, and this influence can only deepen as the HDP here moves forward. The Croatian Weekly, for example, already circulates in the United States and Western Europe, and this aspect of the H DP’s work will certainly develop.

The HDP as a whole is not a Marxist organisation. It is a revolutionary nationalist movement that is strongly influenced by the progressive struggles going on in the world today. The HDP’s orientation is bringing many of its members towards Marxism, and our collaboration can only take this process further.

The HDP is not clear on every single question of the day. There are some of their positions or formulations with which we would disagree. But our method is not to make a list of perfect Marxist positions, tick off those which the HDP supports, and then give them a score. That would be an utterly sterile and sectarian approach.

The essential thing is to recognise their positive evolution. This was the general framework in which we approached Solidarity in Poland. They used some equivocal formulations, their international positions were often naive, and they never came out for the revolutionaries in El Salvador. But we grasped the thing whole, understood the experiences which had made them, and saw the profoundly progressive content of their struggle.